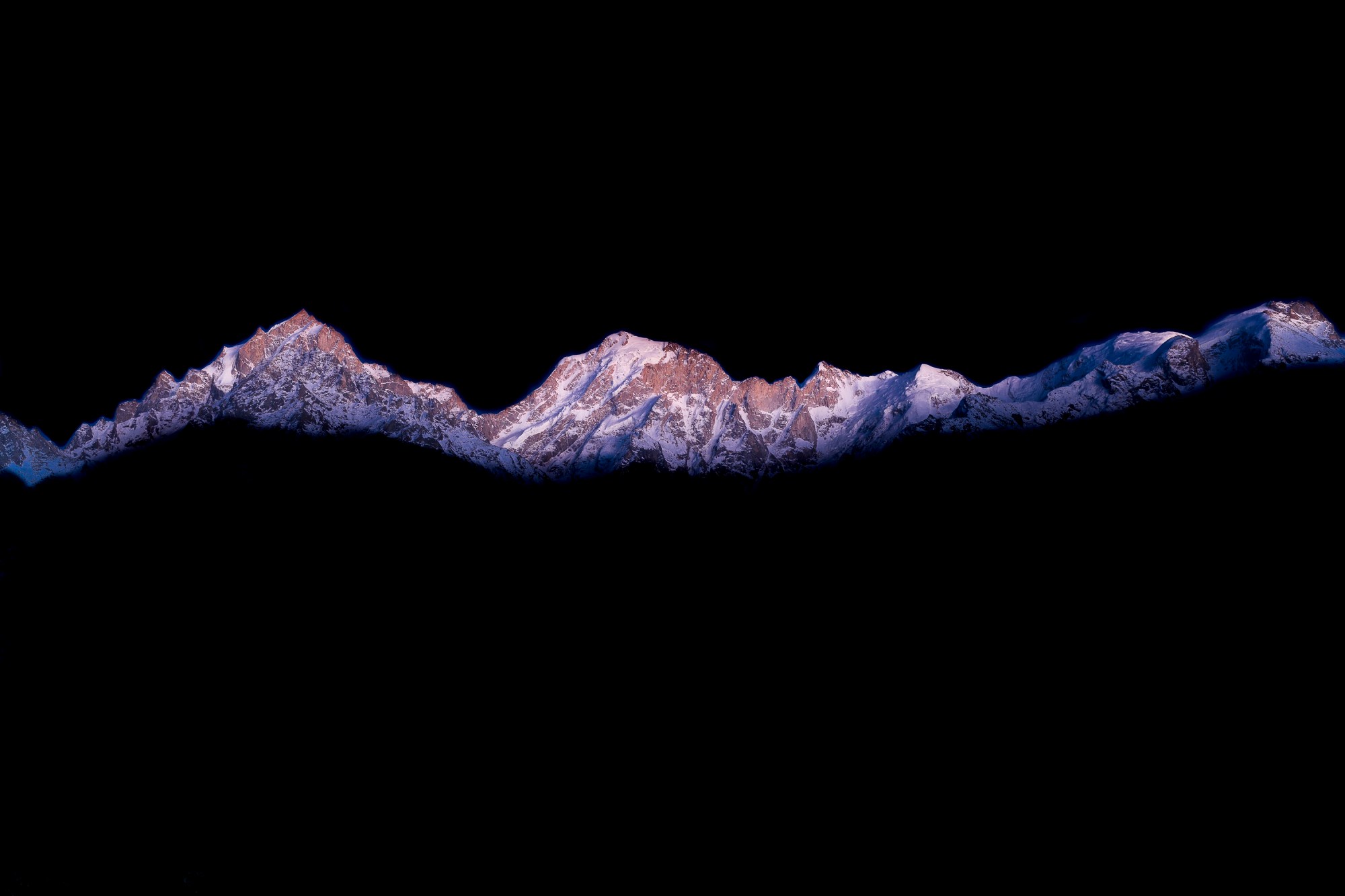

Kinnaur Himalaya, where God and Men meet

From the very beginning I decided on conducting research, rigorously on the field and in a sufficiently remote area. As I had been dealing with the Indian subcontinent, I went for the Himalaya, a geographic area that had always enormously fascinated me ever since I was a kid dreaming to “be a journalist, just like Indiana Jones”. Luckily, after three decades my thoughts had become slightly clearer, and I took my decision with a clear head: to conduct ethnographic research in order to assess the religiousness of the villages of Kalpa, Roghi and Chiktul, in the tribal district of Kinnaur in Himachal Pradesh (India), on the border with Tibet. During office hours I presented the idea to my supervisor who approved it and recommended and entrusted me to the “treatment” of Stefano Beggiora, a doctoral student at the time, and my designated assistant supervisor. Despite Beggiora’s kindness and precious help – an expert in Shamanism and tribal cultures of the Indian subcontinent -, no one in the faculty had ever worked in Kinnaur, and therefore, excluding five or six relatively dated books which I had brought along with me from a previous journey to New Delhi, I had no written information on the area at my disposal. I also knew very little, if nothing at all, about the religious practices of Kinnaur, described as a hybrid of oracular practices and indigenous animism, influenced by the rÑyingmapa buddhism of Tibetan origin.

I wasn’t yet 25 when the moment arrived to leave, alone. Needless to say I was exceedingly excited at the prospect of living for a trimester in a Himalayan village, at 3000 metres above sea level, to work on my research. Despite the limited cash, every penny being accounted for, I tried to organise every single detail all the same, predicting the predictable. This excluded the group “farewell” my friends had in store the night before my departure. “At 4 in the car, on time!” my brother had warned me sternly seeing me go out “for a beer”. I returned three hours before my alarm was due, filled with my friends’ affection, keen to see me miss my flight. For the record, I was able to sober up from that affection only two days after my arrival on Indian soil, when I got on the train that from New Delhi Railway Station brought me to Shimla, a necessary stopover on the way to Kinnaur.

It is impossible to summarise in a single piece three months of work, followed by three more weeks in 2005 for video shoots. Then back again in 2018 for elevn weeks and one month in 2019. In certain places and with the right conditions, the intensity of a single day can fill the same space of an entire week.

field work on the border with Tibet

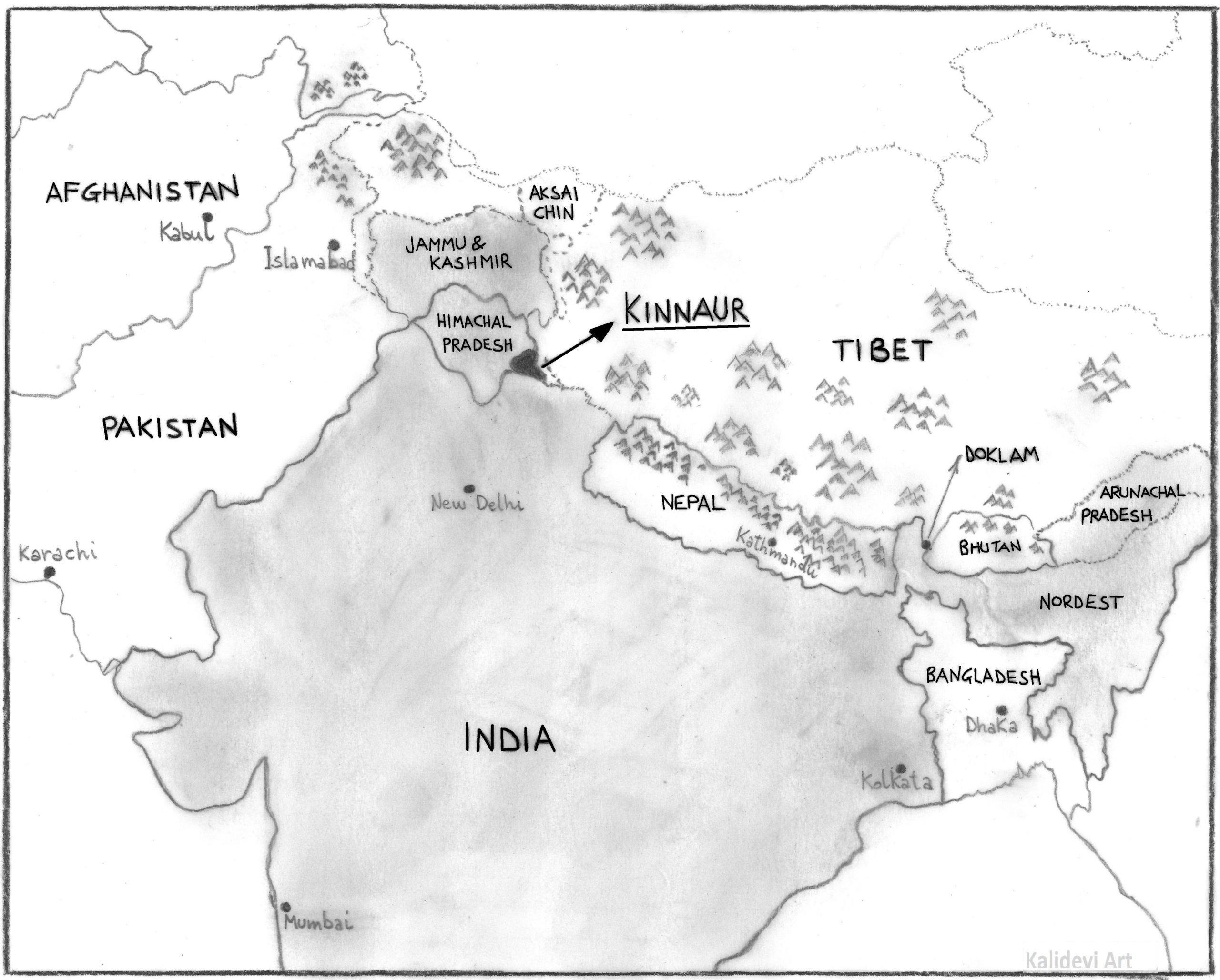

I had been in Kinnaur for two months in order to research local religious practices, concentrating on the grokch, the oracles of area. A little further east, where the Spiti river flows into the Sutlej, runs the Line of Actual Control, the border separating India from the Tibetan plateau and the chinese troupes. The land of the grokch is isolated and steep, removed from the tourism that for the past decades has poured travellers and mystics not far away, around Manali or McLeod Ganj, seat of the exiled Tibetan government.

The Kinnaur region comprises the north-eastern corner of Himachal Pradesh. It is an isolated, jagged and mountainous area expanding on either side of the Sutlej, a river that from the bulk of Kinner Kāilash, crosses the entire chain of the Himalaya down to the plains of Punjab. 80 km long and 55 km wide, the district of Kinnaur borders that of Lahul and Spiti (Himachal Pradesh) to the north, Tibet to the east, the district of Shimla (Himachal Pradesh) to the west, Garhwal (Uttarakhand) to the south, and Manali (Himachal Pradesh) to the south-east. Kinnaur is divided into three distinct geographic physical units: the northern part which includes the last 30 km of the river Spiti until it flows into the Sutlej, and extending up to the conjunction with the river Ropa; the southern district which includes the expanse of land from Karcham up until the border with the Shimla district, and makes up the most fertile area, at a lower altitude. Finally, the central part which includes all the territory characterised by the Himalyan chain as well as the valley of the Baspa river, which comprises the southern offshoot of the group of the Kinner Kāilash and the northernmost peaks of the Dhauladhar chain.

In order to carry out my work I decided to start from the central part of the district. Tourist accommodation in Kalpa was sparse and in poor conditions, so I lodge in the house of CP, a solid building of stone and wood built following traditional standards. All around me the expanse of fruit trees dives deep into the valley below that splits Kinnaur in two. Beyond the seasonally worked lands lie vast expanses of forest and high altitude pastures, dominated by the giant of the Leo Pargial (6,791 metres), the highest peak in the district. However, the main summit is that of the Kinner Kāilash (6,050 metres), a transposition of the Tibetan Kāilash of the same name, believed to be the seat of the gods.

To me the village of Kalpa felt a lot like a basecamp. It rises in a strategic position over an agricultural plateau, point of departure and arrival for the legendary himachali buses. All around are expanses of devadar forest, the himalayan cedar tree, its name, of Sanskrit origin, meaning “wood of the gods”. CP’s house lay on the outskirts of town, and is touched by the Hindustan-Tibet road, an ancient caravan route used in the past as a link between Tibet and the Gange’s plain. Here, in the shadow of the Kinner Kāilash, women and men lead a life tied to moon cycles and the seasons, on which depend crops and pastures, still today the main economic activities. For centuries, before the Indo-Chinese crisis and the closing of borders, together with the loads of salt, wool, and precious stones, the long lines of yak arriving from the Tİbetan plateau carried with them the “bon” and buddhist teaching, while hindū influences travelled in the opposite direction.

One of the main representatives of local religious tradition is Gopal Chand. A minute person with a sinewy frame, able to convey a sense of strength and decision at every occasion. Gopal’s story is representative of local knowledge. To understand it at least in part I had to devote many hours and required the patient mediation of Kaju. Gopal was 17 the day he was raptured. It was evening and he had been out when something took control over his body, driving its movements. One step at a time, in a state of semi-consciousness he reached the temple which lay on a rise not far from the centre of the village. It was here, where local religious practices are still held today, that he united for the first time to his divinity of reference. The intense trembling spread from the hands to the rest of the body, in a crescendo which culminated in sudden backwards jerk of the head. Then he fainted. Dozens of stunned people surrounded his defenceless body, still shaken by the trance, powerless before such a manifestation of force with which no one would have dared interfere. The signs were clear: it had been an rapture of initiation. Gopal had been chosen, and for the rest of his life he would serve as the oracle of Naranas, the warrior god. He had become a grokch, the link between oracle shaman, able to self-induce into a trance and become possessed, carrying out exorcisms and divinations. Almost four decades have passed since that night and today Gopal is one of the most powerful grokch of the Sutlej valley, where day after day the human and divine spheres ally themselves in a perpetual effort to avoid chaos.

To give an example, in Sanskrit texts the idea that god themselves create evil among humans is often recurrent, so as to make humans depend on them (and on the priests). Concurrently in India asura are not always cause of adversities, which are often attributed to the gods. Neither do the latter always represent absolute “good”, nor are destruction, famine and death necessarily viewed as evil-doing. The only given certainty is that sura and asura are always and anyway in conflict. They are similar in nature, but differ as night and day in function. This is why every myth begins with the premise that these two classes of beings are facing one another in battle both on equal footing, if not indeed with the asura starting off with an advantage. The epilogue, however, is always in favour of the sura who defeat the rivals exiling them into the underworld. Yet, some way or another, the non-gods re-emerge to challenge the gods once more. This is probably due to the ritual nature of the myth: every day the same battle must be fought and won as part of a cosmic cyclic conflict for universal supremacy.

The apparent similarity between asura and sura derives from the fact that both share the power of māyā which allows them to take on any form at will. As described in the Satapatha Brāhmana: “among their general features emerge the opposition to light and good, the predilection use of māyā, illusion or deceit, a thundering voice, the ability to take on any form or to disappear; as such they differ from the rākxasa (evil spirits) but not from the gods, except for the first element of the series”.

Also in Kinnaur the various divinities cannot be discerned based on their benevolence or wickedness. The sole qualitative distinction that can be drawn concerns the powers that are useful to mankind and those which are harmful. The crucial difference between asura and sura is strength, so that when the former become powerful (often thanks to their virtues, as is the case in Kinnaur), they must annihilated all the same. Occasionally, however, if the groups that violate the classification cannot be destroyed, they are re-classified, transformed into divinities.

The union between divinity and man is preceded by trance. Tremors begin with the sudden movement of hands, with fingers crossed at the height of the diaphragm. «The god descends from here» Gopal explained as he lowered a hand on his forehead, «I then progressively lose control of my body and I feel nothing else». The tremor extends from the extremities to the thorax, and eventually to the neck. During the descent the grokch’s gaze becomes possessed, his face bright red and he puffs heavily from his mouth, alternating with an unintelligible wheezing. The trance grows in intensity for ten, maybe twenty seconds, then a sudden backward jerk of the head caused the tepang to drop, the Kinnaur hat, and the hair to fall loosely on the forehead. The transfiguration bears witness to the successful rapture. The body of the grokch becomes the divinity itself, therefore each action or uttered word reflect the supreme will. At this moment god and man meet, the first becoming warrior, the second weapon. Relying on unwritten knowledge and a hereditary bond, exorcists, soothsayers and safekeepers of the cosmic order beyond which lies nothing but chaos, they rise as a shield for the community.

During my work in Kinnaur I had the chance to witness a number of oracular sittings. One in particular took place during Phulec, the festival of flowers lasting three days and which occurs every year in the first fifteen days of October. The celebrations take place to mark the end of the harvest, to give thanks for the abundance and to pray for another season of prosperity. As well as to the village gods, the rites are also dedicated to Sāoni, the semi-god of nature and abundance who resides beyond the high pastures, at the glaciers’ limit. According to tradition, this supernatural entity takes on the form of a zomo, a buddhist monk, and on her depends the fertility of the land. The central moment of the feast comes on the last day, when the village god possesses the grokch and performs the poranpagmu, a Kanawari word meaning “inserting the needle”. A very real demonstration of strength that the divinity performs both in honour of Sāoni, and also in order to strengthen the faith among the village inhabitants. After becoming possessed, the oracle – identified with the divinity in that moment – sticks two large pins into his cheeks and nose, removing them only many hours later, at the end of the rite, and without showing any visible wound on his face. But this is another story.

Back to the field in 2018 and 2019

Today Kinnaur is facing an epochal watershed, dictated by the spread of new economic models, above all the spread of the “applecracy”, the apple monoculture. After centuries of agricultural and pastoral activities respecting the environment, the apple business has increased the availability of money a hundredfold, upsetting the perspective of the Kinnauri’s existence. In just one generation, from self-subsistence, gained through the fatigue of hand plowing the soil, to batches of apples negotiated with buyers representing food companies arriving from Indian cities. The “applecracy” has thus created new jobs transforming Kinnaur from a land of diaspora, to a destination for thousands of professional migrants. They come from depressed areas of India and also from Nepal.

The pledge of the “applecracy” is risking a short life due to the water crisis. In Kinnaur the situation is aggravated by the decline of snowfall and the melting of glaciers. The Kinnauri cultivators tackle the rise in temperature by raising the apple orchards to higher ground. It does not matter to them if the orchards replace the primitive woods or the uncontrolled use of the water sources that are already declining. Higher temperatures mean more parasites for which the use of pesticides increases leading to bad health and environmental consequences still to be examined.

Apart from prosperity, the transition taking place is corroding the sense of community. The extended family, which has always been a stronghold of the Kinnauri identity, is progressively being replaced by a mononuclear family. A sense of competition within personal relationships or attention for private property is increasing. Many people are starting to reject local traditions perceived as archaic and far from the style of life diffused by television or smartphone. Traditional wood and stone houses that are symbols of the past and being replaced by concrete blocks to measure the persons success. These buildings are like those in the Indian plains which are not insulated and built without considering the high seismicity of the Himalaya.

The possibility of returning to reason depends therefore on the “apple children”. Thanks to the “applecrazy” the younger generation has the means to study thus understanding the values of the Kinnauri identity. In the same way, the agropastoral activities handed down for centuries and supplanted by apple orchards survive thanks to seasonal migrants. Their history of resiliency indicates their sense of sacrifice, common in this land of oracles, which represents the core of the Himalaya today.